Making the case for financial reforms that deliver justice and sound planning

Abstract

Planning lies at the core of any just and equitable transition. Its credibility depends on the planning process and its efficacy on whether it is supported by communities and can be financed and implemented. National Transition Plans (NTPs), first introduced under Brazil’s G20 Presidency, aimed to chart credible pathways for low-carbon, inclusive development. A year on, under South Africa’s leadership, they remain on the agenda—now questioned for fiscal feasibility, real resource mobilisation and justice. As G20 Finance Ministers deliberate debt relief and global financial architecture reforms ahead of the Leaders’ Summit in December 2025, the effectiveness of NTPs hinges on whether these reforms unlock fiscal space or relegate NTPs to a long lineage of underpowered blueprints.

Diagnosis

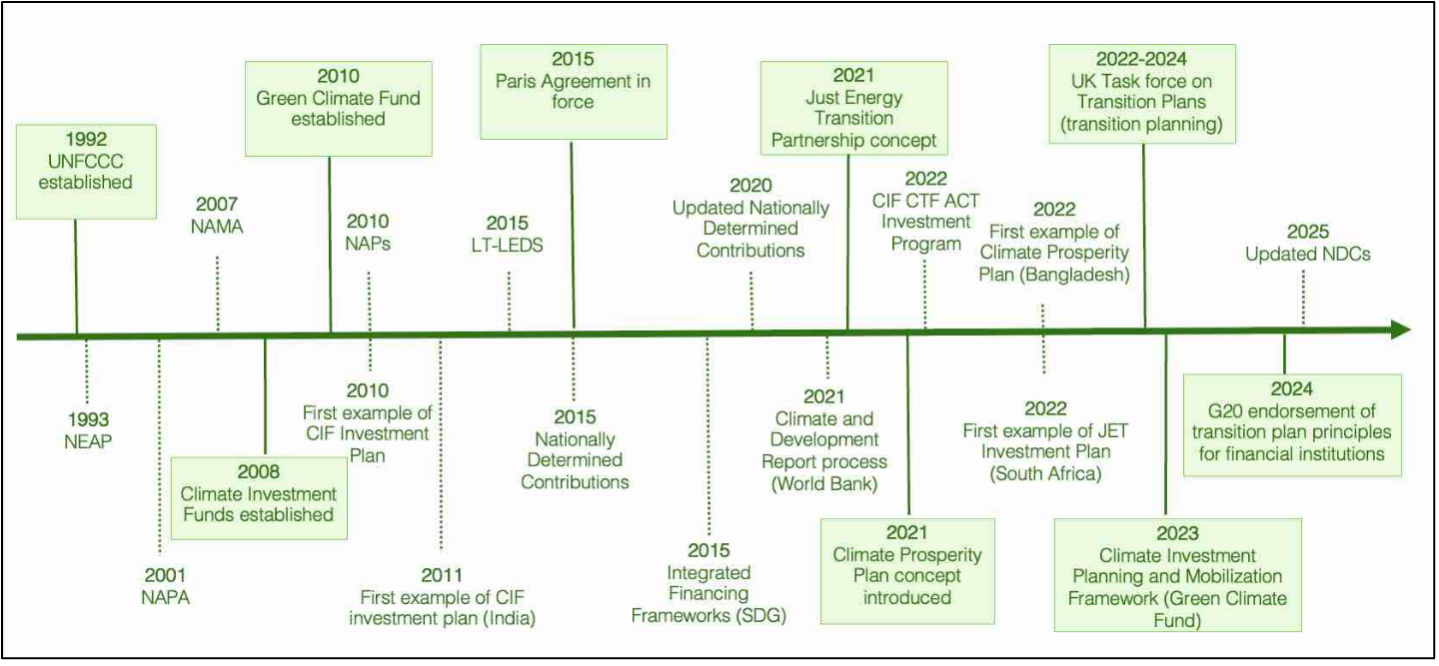

Transitions are inherently systemic, making planning essential to account for their socio-economic consequences. Without such a roadmap, social disruption and economic instability are inevitable. Yet over three decades of climate-related planning reveal that planning alone does not guarantee progress or resource mobilisation. Between 1992 and 2025, countries are continually producing a growing evolution of climate-related plans, ranging from early adaptation and mitigation plans to more recent just energy transition investment plans – with many overlapping across multilateral, bilateral and domestic planning processes. This growing architecture of plans and expectations reflects both ambition and fatigue: how many more plans do we need?

Figure 1: Timeline of Climate-Linked Planning, 1992–2025

Source: Authors’ depiction

This proliferation raises an uncomfortable truth: while climate-related investment planning is increasingly procedural, they are not necessarily more effective. Each “new plan” seeks to correct the last, yet few translate into financing or implementation that meets countries’ needs. For many developing countries, an endless trap endures of planning to plan, diverting scarce capacity even as climate impacts intensify, and promised finance remains out of reach.

At the Africa Climate Summit 2025, Rabia convened a dialogue on “To plan or not to plan” to confront this uncomfortable question. A familiar pattern was revealed: plans shaped around donor logic and investor metrics rather than national priorities, where risks are socialised, returns privatised, and justice an afterthought. The discussion concluded that NTPs as a “new plan” proposition will be ineffectual unless it addresses elements such as social safety nets, systemic effects, economic trade-offs, clustering and sequencing of investments and shared risk.

Relevance to G20

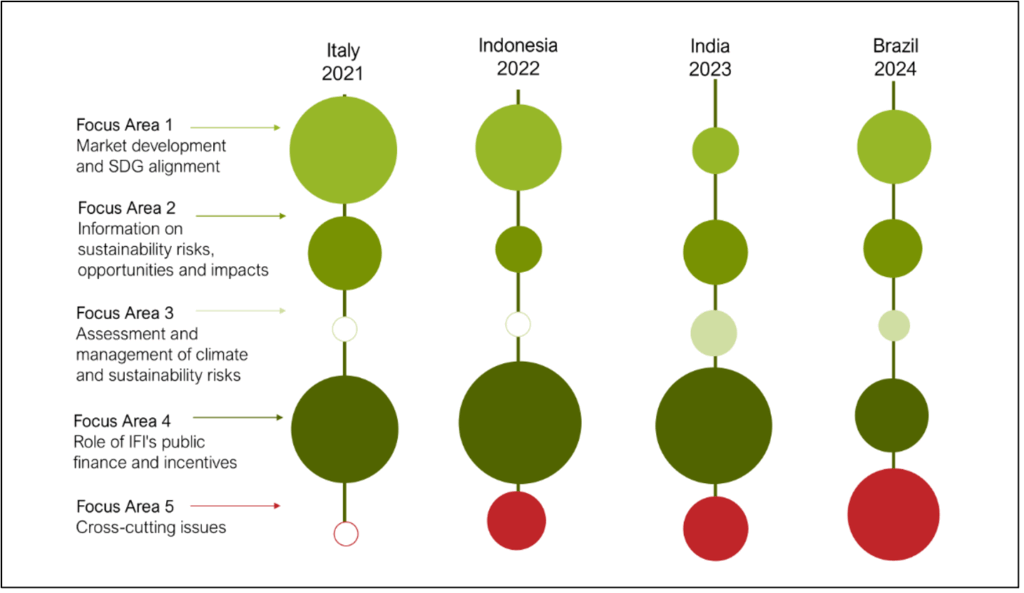

Past G20 presidencies prioritised finance in different ways: While Italy (2021) and Indonesia (2022) leaned toward market alignment and disclosure, India (2023) and Brazil (2024) emphasised public finance and cross-cutting transition issues (UNCTAD, 2025). Now, South Africa’s presidency places financial architecture reform and cost of capital at the heart of its mandate.

Figure 2: G20 finance focus across the Sustainable Finance Roadmap (2021-2024)

Source: Authors’ depiction

The July 2025 G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Communiqué affirm commitment to debt sustainability and MDB reform. Yet these reforms remain detached from the planning processes they are meant to enable. Reform creates fiscal space, but planning determines how that space is used, which needs to be just and dignified by design. Reforms without consideration of planning and implementation are directionless; plans without finance are powerless.

Like many plans before them, NTPs depend on fiscal space and concessional flows. But by design, transition plans differ substantively: requiring emphasis on livelihood impacts (just transition), disruption to economic systems, underpinning revenue models clarified and integration of fiscal and developmental dimensions. All of which are absent in earlier iterations. This gives NTPs a real chance to bridge intent and impact, if the financial reforms on which implementation depends are transformative and systemic. Recognising this circular interdependence, where financial reform enables planning and planning gives purpose to financial reform, is essential.

Recommendations

Several opportunities face the current G20 Presidency to advance the financial reform agenda towards:

- Instilling financing principles: The status quo is a push towards financial reform that only layers justice-oriented themes onto established market logic. G20 must prioritise the inevitable social and economic disruptions and ensure financial design is grounded in justice and dignity by design rather than appended as intent.

- Re-framing the risk logic: The grammar of de-risking private capital through public support remains intact as a proposition within the G20 – which is disconnected from domestic fiscal capacity. This limits the scope for genuine sharing of risk and reward. G20 must ensure affordable finance in local currencies, lower debt burdens, and recognition that fiscal austerity and justice cannot coexist.

- Rebuilding transparency and accountability among rights-holders: Procedural approaches to transparency prevail. Transparency is a precondition for trust, affordability, and ambition. While financial reforms are publicly proposed by all prior G20 presidencies, follow-through is privately designed with muted impacts. The ability to track and trace how reforms support planning and implementation, and benefit all rights holders, is essential.

Authors:

- Dr Chantal Naidoo, Executive Director, Rabia (South Africa)

- Aishwarya Hansen Joshi, Policy Strategist, Rabia (South Africa)

- Penny Winton, Senior Associate, Rabia (South Africa)

- Patrick Lehmann-Grube, Political Economy Analyst, Rabia (South Africa)

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.